(trigger warning: suicide, self-harm)

It goes by many names: non-suicide agreement, suicide prevention contracts, no-harm commitments, and various others — non-suicide contracts, in clinical contexts, have been used since 1973 to outline steps that a person must undertake once they become suicidal.

These facts provide the background for the recent uproar involving Batangas State University’s version of a no-suicide contract.

To many netizens in the comment section, the document seems only a convenient means to absolve the institution should a suicide by a student take place. Many voiced their concern that this wouldn’t help at all, or worse, can further aggravate suicidal impulses.

What are no-suicide contracts really for?

Looking at its literature alone, the angry mob seems justified. The document does sound like the school just wants to keep blood off its hands. An emotionally charged topic like suicide, when translated to such legal expressions, will always garner the same reaction. Thus, to weigh the document’s worth is to instead ask: what should it achieve in the first place?

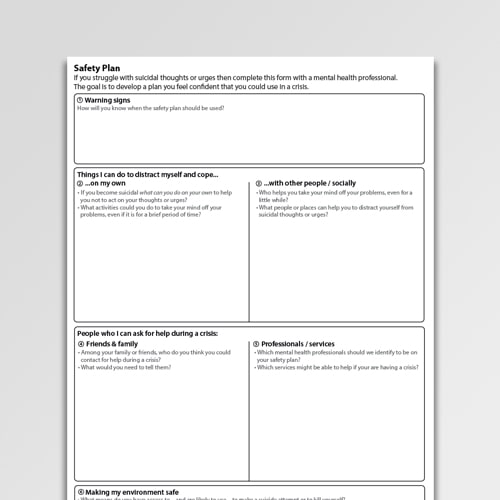

Historically, no-suicide contracts are figuratively written documents that outline concrete, actionable steps that a potentially suicidal person should take when proper supervision or intervention is absent. These serve as a reminder to the person that it is never okay to die by suicide.

Regarding its contents, the document foremost reminds them to call local emergency numbers in case of suicidal thoughts. Then, it presents them with their professional options and provides them with contacts to whom they can anchor their thoughts for the moment.

These terms are thoroughly administered and explained by a licensed clinician, and the document is finally signed only when the same is present.

Anyone can refuse to sign such a document, in which case they are suggested to discuss special terms that they can mutually and overtly agree with their clinician.

Do no-suicide contracts really work?

No ample or reliable data can be found supporting the effectiveness of no-suicide contracts. This figures, given that no-suicide contracts are confidential documents (and should remain so).

Its statistical efficiency is also clouded by the ethical and conceptual dilemmas rising not from the document itself, but from its potential (mis)use — by the administering clinician, by the signing individual, and by the overseeing institution.

First, not all clinicians are trained to administer the document, much less comply with it.

The mere discussion and negotiation of a no-suicide contract influences therapeutic alliance. This means the signature is virtually irrelevant in the providence of medical intervention. Thus, signing this document should not affect the level of clinical care a potentially suicidal individual deserves.

Also, it has to be said that a no-suicide contract should not coerce a potentially suicidal individual into receiving care, nor should it provide false reassurance to the clinician administering the same.

Second, it may unnecessarily paint the picture of suicide as black and white, with acceptance and refusal being the foreground for prevention and aggravation.

This is not and should not be the case. A potentially suicidal person may choose to sign the document just to gain unsupervised freedom due to decreased vigilance, or may refuse to sign to manipulate the clinician to agree with terms more favorable to the patient.

Lastly, the institution that intervenes in the administration of the document — in this case, Batangas State University — can also affect the individual’s perception on its usefulness.

Historically, no-suicide contracts have been implemented within professional settings, setting the precedent that treatment and care are provided only to prevent untoward incidents that may stir criticisms, and not for actual individual relief.

How BSU’s no-suicide contract can be made better

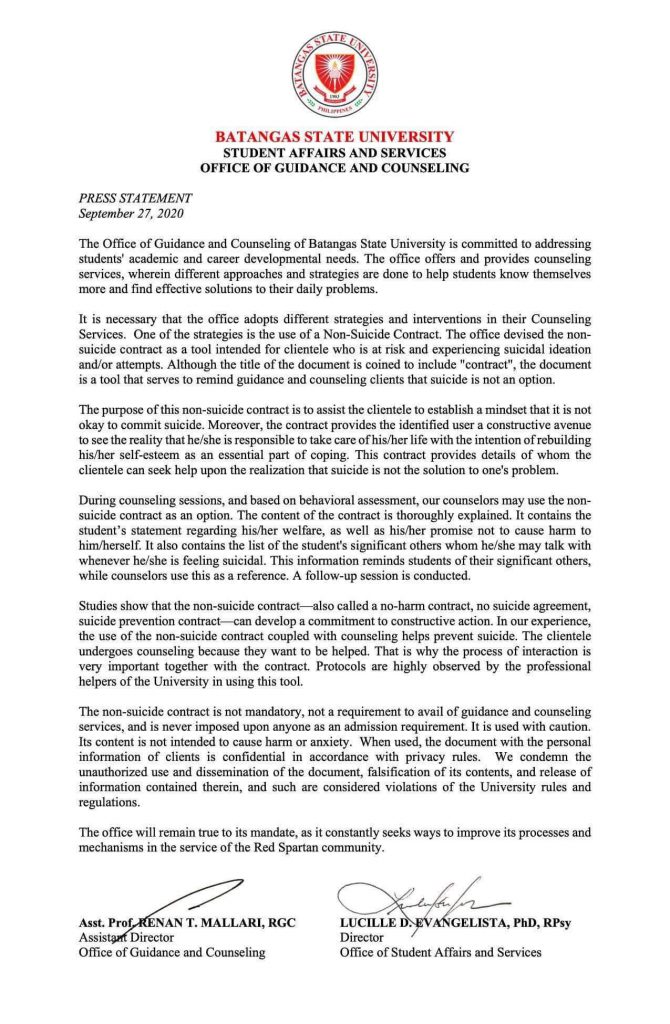

After drawing flak for the document, Batangas State University released a statement justifying its no-suicide contract:

Despite a flurry of opinions from various medical practitioners, they all agree on one criterion: that no-suicide contracts should be specific, individualized, collaborative, and context-sensitive. It should not be mandatory, and should not be a first resort.

For starters, the school can stop calling it a contract and instead use lighter words like “pact,” “agreement,” or even “promise,” if it works with the audience.

Since the document has neither been proven to be beneficial or detrimental, we offer the benefit of the doubt that BSU’s press statement does exactly what it says. If the document works the way it’s supposed to, then it’s only a single, tiny part of the solution, the rest of which BSU would have to guarantee beyond a piece of paper.

(The author does not claim to be an expert in the field discussed. Inputs were acquired and processed from reputable resources and medical journal online. If the reader experiences suicidal thoughts at any degree, they are suggested to reach out to medical professionals, or to contact the following suicide prevention hotlines: In-Touch Crisis Hotline: (+63 2) 8893-1893 / 0917-863-1136 / 0956-053-4257; National Center for Mental Health Crisis Line: 0917-899-USAP (8727) or 8989-USAP (8727) )